The Minnesota Historical Society has mounted an engaging exhibit about the Dakota War that erupted in the summer of 1862 in the Minnesota River Valley. There is nothing flashy about the exhibit itself—just text and maps and a few photos. It’s the events themselves that are engaging. To their credit, the designers of the exhibit have brought those events to the forefront, examining them from various perspectives in an effort to get a “true” picture of what really took place, and why, with nary an interactive kiosk or a “talking head” in sight. It’s a harrowing and heart-rending tale, to say the least.

I first heard about the war, formerly known as the Sioux Uprising, when my sixth-grade class took a field trip to Fort Ridgely in 1966. Since that time, my attitude toward it hasn’t really changed: the Indians got screwed, the settlers got massacred. Neither outcome is “acceptable,” as they say nowadays, but that’s what happened, and there’s little point trying to figure out how things might have been different. You accept and ponder history, or you ignore it. Or you twist it to suit your own agenda.

If we were to put the issues that spurred the war in a chilly, abstract light, we’d say that different land use strategies lay at the root of the conflict. The Dakota were a semi-nomadic people who sustained a modest population on a vast tract of land by means of hunting. The whites were interested in supporting a much larger population base by means of agriculture and commerce. At times the “needs” of incoming settlers is described in terms of wanton exploitation and Manifest Destiny. It may be useful to remind ourselves, as we read about these events, that many immigrants were humble folk, escaping starvation or persecution in Europe, or looking for a new life where the soil had not yet been depleted. At a slightly earlier time, a million people died in Ireland in a single year following a failure of the potato crop. More than a million escaped to start new lives in America.

In any case, the Dakota found metal knives and kettles and guns useful—especially considering that their traditional enemies, the Ojibwe, already had quite a few of them. They also enjoyed the tobacco, and were all too susceptible to the illegal alcohol that was widely available. The two nations had been engaged in commercial relations for generations.

In 1851 several treaties were signed giving whites title to large swaths of tribal land. The Indians got $40 a year each, while retaining title to a relatively small strip of land in the Minnesota River Valley.

I’d like to know how much $40 was worth back in 1852. That would be interesting. I’ve read some accounts of Dakota hunting parties, and that way of life hardly sounds idyllic to me.

I’d also like to know how the U.S. Congress could modified the terms of a treaty after it had been signed. I've never seen a proper explanation of how that works!

Parts of the exhibit probe in detail how badly the Bureau of Indian Affairs behaved in handing out the annuities, bringing out nuances I’d never heard before. Yet it surprises me that at this late date, no one seems to know for sure why the annuities were late in coming that year.

Other displays examine the formation of new warrior societies among the Dakota in the spring and summer of 1862—societies that explicitly excluded any males who had cut their hair, cultivated a field, or in some other way taken up the white man’s way.

Herein lies the second major source of the conflict. Some groups among both the Dakota and the whites felt that the only way to resolve the issues between the two parties was genocide. The remark of governor Alexander Ramsey, that all Dakota people "must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of Minnesota" is often quoted. The evidence suggests that the Dakota war societies had the same idea, though in reverse. One gruesome statistic presented in the exhibit is that 30 percent of the people killed by the Dakota during the uprising were under ten years of age.

Herein lies the second major source of the conflict. Some groups among both the Dakota and the whites felt that the only way to resolve the issues between the two parties was genocide. The remark of governor Alexander Ramsey, that all Dakota people "must be exterminated or driven forever beyond the borders of Minnesota" is often quoted. The evidence suggests that the Dakota war societies had the same idea, though in reverse. One gruesome statistic presented in the exhibit is that 30 percent of the people killed by the Dakota during the uprising were under ten years of age.Many Dakota were appalled themselves by such barbarity, of course. Even Little Crow, the reluctant leader of the revolt, urged his troops to stop killing women and children and start “fighting like white people.”

It may abe less dramatic, but perhaps equally barbaric, to refuse credit to starving Dakota families when everyone knows the funds are on the way.

One great tragedy of the conflict that tends to get overshadowed is the injustice done to Dakota people who had no interest in warrior societies or genocide or revolt. These men and women had often successfully adapted to a more sedentary way of life; in many cases they’d even adopted the white man’s religion. (Many Dakota lost their new-found faith only when they could no longer avoid noticing that very few of the whites actually took Christian values seriously.)

During the revolt these assimilated Dakota individuals guarded and protected the whites, many of whom they’d come to like and respect. They were targeted by the belligerents among their own people, because they, too, represented a threat to the success of the uprising. Yet all too often, once the fighting was over, these individuals were lumped in with the Dakota braves and sent to languish, and often die, in God-forsaken prisons in Iowa or Nebraska.

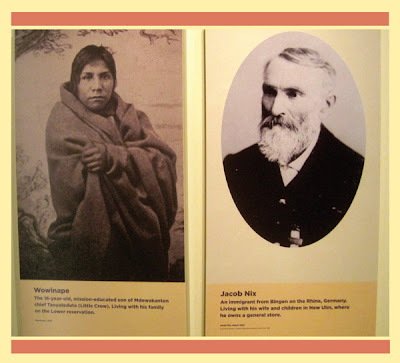

The stories of individuals from every side of the conflict are well-told in the course of the exhibit. One small display case contains 3x5 cards on which a woman who was only six years old at the time of the revolt later recorded the fate of anyone involved whom she could locate and interview.

It’s easy to see that the historical society has spent a lot of time thinking about the best ways to present this dreadful and fascinating episode in the state’s history, which, in the minds of many individuals, both Dakota and white, remains a very personal source of righteousness, anger, or anguish. A number of events will be taking place in August which you can find out about here.

No comments:

Post a Comment